Why Did Houston Decide to Flood the City Again

Houston, America's fourth-largest city, is struggling — like many others — to cope with a new reality of stronger and more frequent rainstorms.

Three major storms have devastated greater Houston since 2015. The first two flooded virtually 16,000 buildings.

More than a third of the properties that flooded in Houston's Memorial Day 2015 and Taxation Day 2016 floods are located outside areas that the Federal Emergency Management Agency deems to be at high take a chance of flooding.

More than than a tertiary of the properties that flooded in Houston's Memorial Day 2015 and Revenue enhancement Day 2016 floods are located outside areas that the Federal Emergency Management Agency deems to be at loftier adventure of flooding.

Coastal prairie, which can assistance protect against flooding, once covered much of Harris County, home to Houston. But real estate development is replacing information technology with non-absorbent physical.

Longtime Harris County Flood Command Chief Mike Talbott, defying scientists, says new development has non increased flood risk.

The northwest Houston suburbs around Cypress Creek are growing rapidly. Scientists and longtime residents say all the new development has made flooding worse.

The northwest Houston suburbs around Cypress Creek are growing chop-chop. Scientists and longtime residents say all the new development has made flooding worse.

Fifteen years ago, Tropical Tempest Allison flooded 73,000 residences in the Houston area and killed 22 people. It is the worst rainstorm to befall an American urban center in modern history.

Fifteen years ago, Tropical Storm Allison flooded 73,000 residences in the Houston area and killed 22 people. It is the worst rainstorm to befall an American city in modern history.

As the Cypress Creek area has grown, developers continue to build homes and businesses in areas that FEMA says are at increased risk of flooding. Many of those flooded this yr.

As the Cypress Creek area has grown, developers proceed to build homes and businesses in areas that FEMA says are at increased risk of flooding. Many of those flooded this year.

The Thou Parkway is a new highway loop that will eventually circle around Houston. Information technology was built because of the exploding population and business concern growth on the outskirts of the metropolis, especially in the Cypress area.

The Grand Parkway is a new highway loop that will eventually circle effectually Houston. It was built because of the exploding population and business organisation growth on the outskirts of the city, particularly in the Cypress area.

The Addicks and Barker reservoirs were built in the 1940s to protect key Houston, but homes and businesses now surroundings them. On Revenue enhancement Day 2016, so much h2o filled the aging reservoirs that some of those homes were put at hazard.

The Addicks and Barker reservoirs were built in the 1940s to protect fundamental Houston, but homes and businesses now environs them. On Tax Day 2016, so much water filled the aging reservoirs that some of those homes were put at adventure.

An old planning map shows that the federal authorities had hoped to build a levee in front of Cypress Creek, to prevent its overflow from threatening the reservoirs. But time, money and politics got in the way, and information technology was never congenital.

An old planning map shows that the federal government had hoped to build a levee in front of Cypress Creek, to prevent its overflow from threatening the reservoirs. But time, coin and politics got in the way, and it was never built.

More than 2,000 miles of natural bayous run through Harris County, helping carry floodwaters to the Gulf of Mexico. The Harris County Overflowing Command District aims to widen these bayous, just has washed little to rein in evolution.

More than than 2,000 miles of natural bayous run through Harris Canton, helping carry floodwaters to the Gulf of Mexico. The Harris County Flood Control District aims to widen these bayous, but has done fiddling to rein in development.

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Twenty-four hour period Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Day Floods |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Taxation Day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Twenty-four hours Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-yr Flood Zones |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Twenty-four hours Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial 24-hour interval Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Flood Zones |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Mean solar day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Overflowing Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Flood Zones | |

| Remaining Coastal Prairie every bit of 2010 | |

| Country newly adult betwixt 2001 and 2010 |

| Remaining Coastal Prairie as of 2010 | |

| Land newly adult between 2001 and 2010 |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Overflowing Zones | |

| Remaining Littoral Prairie as of 2010 | |

| Land newly developed between 2001 and 2010 |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Revenue enhancement Solar day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Flood Zones |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Mean solar day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-yr Flood Zones | |

| Buildings flooded in 2001 TS Allison |

| Buildings flooded in 2001 TS Allison |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-twelvemonth Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Flood Zones | |

| Buildings flooded in 2001 TS Allison |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Flood Zones |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Taxation Day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Twenty-four hour period Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Overflowing Zones |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Taxation Day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Inundation Zones |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Tax Mean solar day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Day Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Alluvion Zones |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Taxation Twenty-four hour period Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial Twenty-four hours Floods | |

| FEMA 100-twelvemonth Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-year Flood Zones |

| A 1940 map shows plans for a levee south of Cypress Creek. It was never built. | |

| Buildings flooded in 2016 Taxation Day Floods | |

| Buildings flooded in 2015 Memorial 24-hour interval Floods | |

| FEMA 100-year Flood Zones | |

| FEMA 500-twelvemonth Overflowing Zones |

A 1940 map shows plans for a levee southward of Cypress Creek. It was never built.

| A 1940 map shows plans for a levee due south of Cypress Creek. It was never built. | |

| Major rivers and streams in Harris County |

| Major rivers and streams in Harris Canton |

| Major rivers and streams in Harris County |

Boomtown, Inundation Town

Climatic change will bring more than frequent and violent rainstorms to cities like Houston. Just unchecked development remains a priority in the famously un-zoned city, creating short-term economic gains for some while increasing flood risks for anybody.

0

An aerial shot of downtown Houston during the "Tax Solar day Flood" in April. (Jordan Anderson/DoubleHorn Photography)

This is function of a serial on Houston's flood risk. Read nigh why Texas isn't ready for the next big hurricane.

HOUSTON — For the tertiary time in viii years, water gushed into Virginia Hammond'south northwest Houston habitation.

1

It was 2 a.m. on April 18. Over the adjacent several hours, her two granddaughters — ages 12 and 15 — perched on tables, scared to put their anxiety in the dark gray floodwater rising beneath them. It nearly topped 3 feet.

"They couldn't get in the beds because the beds were wet. They couldn't get to the bath because the water was over the toilet bowl," Hammond recalled.

"We were in at that place, well, trapped."

The storm that pummeled Hammond'southward modest brick dwelling — nicknamed the "Tax Twenty-four hour period" inundation because it fell on the borderline to file federal income taxes — came just 11 months after another, on Memorial 24-hour interval 2015, that besides crippled the city. Together, the floods killed 16 people, inflicted well over $one billion in damage and provoked an unprecedented uproar from Houstonians, some of whom are at present suing the city over chronic flooding problems. A calendar month after the Tax Day inundation, another mega-storm striking the urban center, dumping well over a human foot of rain on parts of Harris Canton, home to Houston, in 24 hours.

two

The area's history is punctuated past such major dorsum-to-dorsum storms, but many residents say they are becoming more frequent and astringent, and scientists agree.

"More than people dice here than anywhere else from floods," said Sam Brody, a Texas A&K University at Galveston researcher who specializes in natural hazards mitigation. "More property per capita is lost here. And the problem's getting worse."

Why?

Scientists, other experts and federal officials say Houston's explosive growth is largely to arraign. As millions have flocked to the metropolitan surface area in contempo decades, local officials have largely snubbed stricter building regulations, allowing developers to pave over crucial acres of prairie land that once absorbed huge amounts of rainwater. That has led to an excess of floodwater during storms that chokes the city's vast bayou network, drainage systems and two huge federally owned reservoirs, endangering many nearby homes — including Virginia Hammond'south.

A bloated Buffalo Bayou in fundamental Houston is shown during the Tax Day 2016 flood. The waterway runs through downtown Houston. (Dominic Lopez)

3

On top of that, scientists say climatic change is causing torrential rainfall to happen more ofttimes, pregnant storms that used to be considered "once-in-a-lifetime" events are happening with greater frequency. Rare storms that accept simply a miniscule take chances of occurring in whatsoever given year take repeatedly battered the urban center in the past xv years. And a significant portion of buildings that flooded in the same time frame were not located in the "100-twelvemonth" floodplain — the expanse considered to have a one percent chance of flooding in any given year — catching residents who are not required to conduct overflowing insurance off guard.

4

Scientists say the Harris Canton Flood Control District, which manages thousands of miles of floodwater-evacuating bayous and helps enforce development rules, should focus more on preserving green space and managing growth. The City of Houston, besides. And they say everyone should plan for more torrential rainfall considering of the changing climate. (A host of cities in the U.Southward. and effectually the globe are doing so.)

But canton and city officials responsible for addressing flooding largely refuse these arguments. Houston's two top overflowing control officials say their biggest challenge is not managing rapid growth but retrofitting outdated infrastructure. Electric current standards that govern how and where developers and residents can build are by and large sufficient, they say. And all the recent monster storms are freak occurrences — not harbingers of global warming or a sign of things to come.

The longtime caput of the alluvion control district apartment-out disagrees with scientific evidence that shows development is making flooding worse. Engineering science projects can reverse the furnishings of country evolution and are doing and so, Mike Talbott said in an interview with The Texas Tribune and ProPublica in late August earlier his retirement later 18 years heading the powerful bureau. (His successor shares his views.)

The claim that "these magic sponges out in the prairie would have absorbed all that water is cool," Talbott said.

He also said the flood control commune has no plans to written report climate change or its impacts on Harris Canton, the tertiary-nigh-populous county in the United states of america.

Of the astonishing frequency of huge floods the city has been getting, he said, "I don't call up it'due south the new normal." He also criticized scientists and conservationists for being "anti-evolution."

"They have an agenda ... their calendar to protect the environment overrides common sense," he said.

But Talbott best-selling that projects in the works wouldn't come shut to protecting against something like a Tax Day flood. Those include retrofitting old drainage, widening bayous and building more ponds to temporarily shop floodwater.

Buffalo Bayou, in due west Houston, during more normal weather weather condition. (Michael Stravato for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

Meanwhile, the city of Houston'south "overflowing czar," appointed afterward the Tax Day tempest to assess the urban center's flooding bug, appears more receptive to alternative solutions, similar more than greenish space. But Stephen Costello, an engineer and old metropolis councilman and mayoral candidate, has had no upkeep, staff or house timeline. (He expects to hire 1 paid staffer in the coming weeks.)

He also acknowledges his role as more political than action-oriented. He spends much of his fourth dimension consoling angry residents at community meetings and "making house calls." And he is pursuing smaller, cheaper, quick-hit projects.

"I think what people are keenly interested in is making sure that there is a point person that they tin straight their comments to," said Houston'south Mayor, Sylvester Turner, noting the urban center "has never had a chief resilience officer. That indicates in and of itself a major commitment."

But residents who have flooded say they're looking for more than that.

Eight months afterward the Tax Solar day flood, Hammond'southward home is notwithstanding in slaughterhouse, with almost no furniture, kitchen cabinets or place to cook. She wants someone to buy her out, but she'south non optimistic.

"I'one thousand too former to go through this once again," Hammond said. "Information technology'due south very traumatizing."

The New Normal?

For Louise Hansen, the story has been the same every fourth dimension she'south flooded: The h2o starts to creep into her house in the middle of the night.

In 2009 — the commencement fourth dimension her west Houston home flooded later on she moved into it about a decade earlier — she figured it was an bibelot. Then it happened again in 2015. And again in 2016.

Iii times in less than x years — for a home that'due south not in any floodplain identified by the Federal Emergency Management Agency. "It's really paralyzed me," said Hansen, who grew up in the area and is now selling her house just for the lot value. "I just don't recall I can go through some other flood."

Many of Hansen's neighbors, who live in an area of Houston known every bit Memorial City, have had the same experience. They've flooded in 2009, 2015 and 2016, and none of them live in any known floodplain. So they take formed a group called "Residents Confronting Flooding," and recently, the group sued the Urban center of Houston and a local tax reinvestment zone this year, demanding improve drainage.

A portion of Interstate x nigh Memorial Metropolis in west Houston. (Texas Ceremonious Air Patrol)

What'southward happened in Memorial City is chosen "urban flooding." The phenomenon refers to flooding exterior of any known floodplain — in this case, outside the 100-year floodplain, which triggers insurance requirements, or the 500-year floodplain, which has a i in 500 chance of flooding in whatever given twelvemonth. Homeowners don't need insurance to get a mortgage in the 500-year floodplain, but many buy it anyway.

And it turns out that Houston has seen the most urban flooding of any other area in the land in the past iv decades, according to recent analysis by Brody, the Texas A&Thousand scientist.

Scientists say there are a number of likely culprits. Maps showing where the floodplains are may be outdated, for ane thing, and the drainage in this older role of town was probable congenital earlier engineers understood the truthful risk of flooding in the expanse.

Then there are the reasons scientists fear local officials are ignoring.

For one, overflowing planning is still done by looking at what'due south happened in the past. Only climate change means that might non piece of work anymore.

"How practise nosotros decide where the 100-year flood zone lies? Past looking backwards at rain events in the past," said Katharine Hayhoe, a climate scientist at Texas Tech University. "Looking backwards does not work so well if climate is changing."

In general, Hayhoe said, climate change takes the risks that people already face and makes them worse. That's particularly true for Houston because information technology sits so close to the Gulf of United mexican states, where waters have been warming equally the planet gets hotter.

Warm water means more evaporation and more water vapor in the air. So when a storm comes along, there's more than water to option up and dump on nearby land.

"The verbal same storm that comes along today has more rain associated with it than it would accept 50 or 100 years agone," Hayhoe said. "And that's a big function of what happened in Houston" on Tax Twenty-four hours.

There are many ways to measure the frequency of rare storms in an area. The Harris County Overflowing Control District does and then by tracking rainfall totals for the entire county inside a 24-hour menstruum. Based on that data, which dates back to 1989, the canton has been striking with 8 rare storms.

V of those storms are considered to have a 1 in 100 chance of occurring each year, including the rains that hit in May of this year. Another iii are considered to be even rarer, including the Tax Day storm in April of this yr.

The alluvion control district could not provide data in time for this story on rainfall that occurred over a 12-hr menstruation, rather than a 24-hour period. Just it nevertheless confirmed that the number of rare storms would be higher. (Enough pelting barbarous during the Memorial Day 2015 storm over 12 hours to classify information technology every bit a 100-year result.)

five

But Talbott doesn't think Houston'due south most recent back-to-back torrential floods are indicative of climate change, or that studying its potential impacts should be a priority for the Harris County Alluvion Control District.

"We've had heavy back-to-back rainfalls before," he said.

Of the depression probability that two 100-year storms hit within weeks of each other, he said, "You can flip a coin and come up heads 10 times in a row." (The flood control district is partially funding a study that will assist decide whether rainfall totals should change for what are considered to exist rare storms.)

He also downplayed the human touch of the Tax Day tempest, pointing out that no one drowned in their domicile — only in flooded underpasses they drove into — and that the resulting flood impacted a relatively small portion of the population.

"Every bit bad as the April, the Tax Day flood, was this twelvemonth, if y'all look at the number of people affected in Harris County, it's less than 1 percent of the population. Is the other 99 per centum willing to pay for a much more robust system?" he said.

vi

Scientists also worry that local officials are ignoring another crucial reason Houston is flooding more: what Hayhoe calls "the paving of Houston."

The region was one time home to acres of prairie grass whose roots extended far underground, with a capacity to absorb water for days on end or even permanently. Most of that land has at present been paved over. The Katy Prairie northwest of Houston was in one case well-nigh 600,000 acres of flood-absorbing country; recent development has reduced information technology to a quarter of that capacity, co-ordinate to estimates from the Katy Prairie Conservancy, an advocacy group.

That means the pelting is now falling on what are chosen impervious or impermeable surfaces, like concrete, preventing the ground underneath from absorbing it. So the rainfall becomes "runoff," traveling to wherever is easiest for information technology to period. The water might flow to a nearby stream, merely on its way the water could flood homes, cars and businesses, or the stream might exist overwhelmed by that water, causing more flooding nearby.

In Harris County alone, research by Texas A&M scientist John Jacob shows, nearly thirty percent of freshwater wetlands were lost between 1992 and 2010, a effigy he calls "unconscionable."

As wetlands have been lost, the amount of impervious surface in Harris Canton increased by 25 per centum from 1996 to 2011, Brody said. And there's no way that engineering projects or flood control regulations have fabricated upwards for that change, he said.

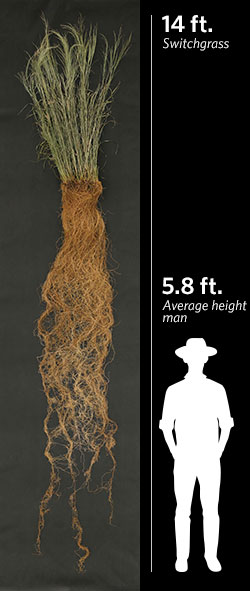

Absorbent prairie grasses such as switchgrass tin grow roots up to 15 feet long. Researchers say the developed landscapes that supplant it — such as suburban lawns — tin't compare with its ability to absorb water and protect against floods. (photograph: Steve Renich, courtesy of The Land Establish, analogy: Alberto Cairo)

Betwixt 2001 and 2005, his inquiry found, the loss of flood-absorbing land forth the Gulf of Mexico increased property damage from floods by about $half dozen million — much of that outside floodplains.

"At that place's no doubt that the development ... that we're putting in these flood-prone areas is exacerbating flooding over time," Brody said. "There's a huge body of research out there beyond Houston, beyond the world" supporting that argument.

Research past Talbott's own Harris County Flood Control District points to the effectiveness of prairie grass to absorb floodwater. "The restoration of ane acre of prairie," a 2015 written report by the district wrote, would offset the extra volume of runoff created by two acres of unmarried-family homes or one acre of commercial property. (The district says that data is preliminary.)

But Talbott and his successor, Russ Poppe, don't buy the research.

Developers accept to follow regulations that should contrary the effects of paving over wetlands, they both argued. That includes building what are called detention ponds, which tin temporarily store rainwater when it falls on pavement and isn't absorbed into the ground.

These regulations first went into effect in the mid-1980s. Talbott and Poppe claim that all evolution since then has not contributed to any boosted flooding.

Both insisted the rules are so effective that an acre of commercial strip mall would discharge stormwater at the same rate every bit an acre covered in prairie grass — though non for events rarer than a 100-yr storm. They pointed to a 2011 study deputed past the inundation command district as evidence.

Mike Talbott recently retired later heading the Harris Canton Flood Control District for 18 years. (Michael Stravato for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

But scientists vehemently disagree with those claims. They say the restrictions are inadequate — and loosely enforced — and could worsen the situation for people like Louise Hansen and her neighbors.

7

When developments in floodplains are elevated, they can end up redirecting floodwaters to a nearby neighborhood, causing flooding where it otherwise might not have happened, in areas far outside floodplains. The phenomenon has been acknowledged by FEMA, but it'southward never been fully studied.

Brody said he couldn't be sure that's what's happening to Hansen, but a graduate pupil of his, Kayode Atoba, is researching that very question right now. And Hansen's story is a familiar i.

"I can't tell you how many times I've gotten people calling me saying: 'I've never flooded earlier, I've been here for xxx years, I'm not in a floodplain," Brody said. "And every unmarried time, there's a evolution nearby that's changed drainage ... that story is told every day tens of thousands of times across the country."

Talbott disagreed that elevating buildings could be causing others to flood, and in general, he dismissed what Brody and other scientists had to say about what is causing Houston's flooding problems.

"You need to discover some better experts," he said. When asked for names, he would but say, "starting here, with me."

Not a unmarried scientist or expert of a dozen interviewed by The Texas Tribune and ProPublica shared his view on such matters.

"I don't agree with Mr. Talbott at all," said Phil Bedient, a Rice University scientist. "That is an astounding statement. I don't agree with information technology, and in that location are a lot of other people that don't either."

Hansen, the Memorial City resident, rejects the thought that local officials tin't practise anything to assistance her situation.

8

"I have learned that information technology'south authorities, and things have a very, very long time to get annihilation washed. Merely y'all accept to go on fighting," she said.

Rapid Growth, "Sitting ducks"

Stacey Summers and her hubby sat on their bed with their two small dogs, gazing out the window in shock at snakes pond past in the rising floodwaters. During the Tax Twenty-four hours flood, the h2o rushed into their one-story brick business firm in the northwest Houston suburb of Cypress, in a matter of hours, topping out at nearly a foot.

"It's unimaginable still," said Summers, who evacuated her neighborhood in a canoe, as did many of her neighbors. The creek near her upscale subdivision known as Stable Gate overflowed, flooding near all of the 250 homes in the neighborhood.

The 15-twelvemonth-old Stable Gate subdivision, where Stacey Summers lives, flooded for the first time in April. (Texas Civil Air Patrol)

Information technology was the first time the 15-year-old development had flooded. Just scientists point to the area as one where development has run amok in recent years, putting more people and property in damage's manner.

"Those people upwardly there are sitting ducks," said Bedient, the Rice Academy scientist.

Because all the h2o in the area drains into Cypress Creek, it'southward chosen the Cypress Creek watershed. In the 1990s, as the population in the watershed grew past 35 percent, 2 major floods hit the area — both considered "500-twelvemonth" events, which should have only a ane in 500 chance of occurring in any given year.

9

The back-to-dorsum floods spurred a rowdy, beer-fueled gathering at a local Veterans of Foreign Wars hall in 1998 and, before long after, the formation of the Cypress Creek Flood Command Coalition. The hope was to adjourn further evolution, or encourage more responsible evolution, to help forbid flooding.

But footling changed, even subsequently some other major storm crippled Cypress and the Houston region merely three years afterward — one that scientists say should have served as a wake-up call.

In June 2001, Tropical Storm Allison dumped most 40 inches of pelting on the city in five days, flooding 73,000 residences and 95,000 vehicles. Twenty-two people died, and impairment from the storm was more than $5 billion in Harris County. Information technology likely is the worst rainstorm to ever befall an American city in modern history, according to the inundation command district.

10

Allison was a daze not only because of the extent of flooding but also where it occurred — almost half of the buildings that flooded were exterior floodplains designated by FEMA.

The tragedy prompted FEMA and the alluvion command commune to redraw floodplain maps, which expanded every bit much as 20 percent in some areas. And in conjunction with the city, the district spent hundreds of millions of dollars to improve drainage, widen bayous and build detention ponds to temporarily hold floodwater.

An aeriform view of flooding in Houston from Tropical Storm Allison in June 2001. The watershed that forms White Oak Bayou, which joins Buffalo Bayou here, took the brunt of the storm's rainfall. (Courtesy: Harris County Flood Command District)

But when local politicians tried to modify policies over development, they were met with potent resistance from developers and residents.

The city did pursue a constabulary banning new evolution or major renovations of existing buildings in areas chosen floodways — the most vulnerable parts of the 100-year floodplain that are closest to the bayous. That prompted multiple lawsuits, and the law was ultimately severely weakened past the urban center quango two years later.

However, said Bill White, who was mayor at the time, "It was the near aggressive activity that had always been taken" against such development.

When White's successor, Annise Parker, tried to impose a fee on city residents to pay for drainage improvements, lawsuits followed, likewise. The proposed fee remains in limbo.

The canton'southward development regulations are superior to the city's and take been strengthened over time, said Steve Radack, a longtime Harris Canton Commissioner who represents the Cypress expanse.

Just they have to be economically reasonable, he said. If the rules are too strict, developers volition say "fine, to heck with Harris County. We'll go build in Fort Curve," the canton directly west of Harris County, or wherever else, he said.

In fact, Fort Bend Canton has stricter regulations for developing in the floodplain — and it'southward growing faster than Harris Canton.

Developers at that place must incorporate more green space or detention ponds than in Harris Canton. That'due south because Fort Bend requires them to agree excess floodwater on their backdrop for longer and belch it at one-tenth of the rate in Harris County.

A retention pond on Interstate 10 in Houston is designed to concur backlog floodwater after heavy rains. (Michael Stravato for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

"They still take lots of development, information technology's merely that they know how to practise it," said Phil Bedient of Rice Academy, who helped develop Fort Bend Canton's rules.

Harris County has never prioritized green space, he said, and is now paying the price.

"Mother Nature is wreaking her fury on the county and sending some fairly stiff signals that some things need to change."

eleven

Bedient and other experts also say they wish Harris County had been able to buy out more than homes that take been badly damaged past floods or that are known to overflowing repeatedly. Since Allison, the inundation control district has purchased about 2,400 such properties, mostly with federal money, and after the Tax Day alluvion, the district allocated $15 million of local money for more buyouts. A contempo report past the bureau has identified 3,300 homes that are yet at high risk of flooding and should be bought.

The properties that were caused "will never flood again – the only properties for which nosotros tin can make such a guarantee," according to the flood control district website. "Unfortunately, there notwithstanding remain over 140,000 single-habitation residential parcels identified inside the regulated floodplains."

Scientists and experts say communities need to movement away from developing in the 100-year floodplain, or at least brand the rules for doing so far more stringent. But after Allison, the pace of development in and near floodplains in the Houston expanse only seemed to accelerate — especially in the Cypress Creek area, where at that place was still plenty of cheap pastureland.

The same year Allison occurred, Stacey Summers' neighborhood was congenital. And over the side by side decade, the Cypress Creek area grew even faster than it had in the previous one.

Between 2000 and 2010, it grew by nearly 70 percentage to a population of 587,142 — equivalent to that of Milwaukee. In that aforementioned time period, according to a Tribune/ProPublica assay, the per centum of developed land there jumped from 23 pct to 33 percent.

12

Stable Gate was one of many neighborhoods built in the area after Allison. It wasn't in a floodplain when it was built in 2001, merely new flood maps that took result vi years later placed a big swath of the subdivision in the 100-year floodplain, triggering flood insurance requirements for many residents. Parts of the neighborhood were also placed in a newly expanded 500-year floodplain — an surface area with a smaller but still notable chance of flooding each year.

Summers' domicile ended up in a 500-year floodplain subsequently the new maps took effect. She doesn't need to buy overflowing insurance, but she still carries information technology for about $400 a year. Greg Bowen, president of the Stable Gate Homeowners Association, said the neighborhood "was built on the all-time data they had at the time."

But fifty-fifty with the new inundation maps, development has continued in the 100-twelvemonth floodplains. Since 2010, more 7,000 residential buildings have been built in these risky areas in Harris County, co-ordinate to a Tribune/ProPublica analysis of local appraisal data, forth with more than 1,600 nonresidential buildings.

Bowen said the county and developers are non installing plenty alluvion control measures or ensuring developers follow the rules for building in a floodplain.

"The lesser line is there needs to be more done to keep upward with the growth out in Cypress," he said.

Frank Espinoza recently built 12 homes in the 100-year floodplain along Piffling Cypress Creek, merely a few miles from Stable Gate. Three of them flooded on Tax Day, costing him tens of thousands of dollars to repair.

13

The longtime Houston-area homebuilder finished them anyway, and even though he doesn't have to tell buyers, he said he will to avoid lawsuits. But he doesn't think the homes will flood again.

"I just think it was a freak of nature," Espinoza said, noting the elevations of many of the homes that didn't flood are really lower than the ones that did.

Growth in Cypress and other Houston-expanse suburbs has been so substantial that the state plans to build a tertiary highway loop around the city. When it'southward completed in 2021, the Grand Parkway volition be large plenty to fit the state of Rhode Island inside of it.

14

The highway will cut down on commute times, but critics — including the environmental group Sierra Club, which sued to try to stop its construction — say information technology will encourage even more suburban sprawl and wetland loss and worsen flooding problems.

That new evolution will not just make Cypress more vulnerable, but it besides will impact flooding problems downstream, scientists say. That'due south because in that location is less green infinite to absorb rainfall, causing more than — and faster — runoff into Cypress Creek, which spills into several streams that flow southeast toward downtown Houston and the coast.

Dick Smith, co-founder and longtime president of the Cypress Creek Flood Control Coalition, said his group has worked for more a decade to encourage the county to program for the impact of new growth. He said he'd similar to encounter it act more like Fort Bend County.

But the flood control district has "stiff-armed" them multiple times, he said.

They'll never be able to totally prevent flooding, Smith said, but "they could exercise a hell of a lot amend chore than they're doing."

Smith'south dwelling showtime flooded in 1994, and has since flooded four more times. Tax Solar day was the worst, he said, when 35 inches of water accumulated on his footing floor.

At the raucous 1998 VFW meeting that inspired Smith and his neighbors to form the coalition, he recalled someone demanding they put the local county commissioner's "ass in a boat" to tour the extensive harm.

Near 20 years later, that county commissioner — Radack — is however fielding angry feedback from residents.

At an Baronial town hall, Radack told more than than 300 seething attendees packed into a church auditorium that they were part of the problem. He said information technology all came down to paying for alluvion control projects and said he would vote for a tax increment to do so.

"This is what this is all about," he said, repeatedly. "Government — it takes money."

fifteen

Just residents urged Radack to support stricter development criteria and enforce the existing rules. They also repeatedly said the canton should somehow curb growth outright.

"Just stop building," one woman yelled, inciting thanks.

"A whole lot of yous people live in subdivisions that in many people'south stance should accept never been built," Radack responded. "Merely people accept a right to development. They own the land, if they follow the rules."

"Simply they're not," several people in the crowd shouted in unison.

Asked virtually such sentiments, Talbott said resident expectations are too high.

"I've heard the members of the public say they never want their streets to flood, and they don't desire their houses to alluvion," he said. "That's just unrealistic."

The Reservoir Predicament

sixteen

If development in the Cypress Creek area grew after Tropical Storm Allison, it grew even more than quickly in the surface area around Addicks Reservoir — 1 of two massive World War II-era detention basins meant to protect key Houston from catastrophic flooding.

In 2001, 28 percentage of the state in the Addicks watershed was adult. By 2010, it was 41 percent. And Virginia Hammond's home is perched on the northern edge of the reservoir .

The U.South. Army Corps of Engineers built Addicks and its analogue, Barker Reservoir, in the 1940s after back-to-back mega storms put downtown Houston underwater. At the time, the Army Corps had a singular mission: to protect Houston, which was then some xv miles away from the reservoirs. But 70 years later, achieving that goal has become more hard as Houston's suburban sprawl has encroached on them.

A neighborhood encroaches on the north side of Addicks Reservoir, which is dry out and covered in wooded parkland except during floods. (Michael Stravato for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

During heavy rainfall, the Corps shutters conduits on the reservoir's tall, earthen dams to keep a torrent of water from rushing downwards downward Buffalo Bayou — a narrow, winding waterway that passes through downtown on its manner to the declension.

The reservoirs are dry most of the time, covered in forest and parkland. But Army Corps officials say the amount of water that accumulates in the reservoirs during large storms has increased substantially in recent decades, and takes longer to drain out. That's because much of the open up infinite effectually them has been covered with non-absorbent concrete.

When those pools get as well large, the Army Corps is forced into a precarious balancing act where it has to keep just enough water inside the reservoirs to protect areas downstream while also releasing enough h2o then that surrounding neighborhoods, including Hammond's subdivision, aren't flooded.

"Nosotros're betwixt a stone and a difficult place," said Richard K. Long, who helps oversee the twenty-four hour period-to-day operation of Addicks and Barker for the Corps.

In an platonic world, neighborhoods similar Hammond's wouldn't exist, he acknowledged.

Hammond's neighbor, retired engineer Ali Aumir, whose dwelling house also has flooded three times, agrees: "This whole expanse should never have been built." Long said in that location was no way the Corps — or anyone — could've predicted seventy years ago the kind of growth the Houston area has seen. If it had, he says the Corps probably would've done things differently — bought upwards more land around the reservoirs, for example, or at least acquired easements allowing the agency to flood it when necessary. (The Corps has such legal agreements for most of its reservoirs.)

Streets in the Savannah Estates subdivision in northwest Houston, where Virginia Hammond lives, were still flooded days afterward the Taxation Day tempest. (Texas Civil Air Patrol)

The agency has little to no control over development, though. Long says its easily were tied by local politicians and other factors, including the whims of various presidents and congresses with differing views on how much land the government should ain and who controls the Army Corps budget.

"Today if we were starting over once again knowing what has happened, would our boxing lines exist a petty unlike? Yes, our battle lines would definitely be different. But nosotros don't have that pleasure of doing that," Long said. After the Tax Day storm, the corporeality of water that accumulated in Addicks and Barker reached record highs, forcing the Army Corps to release more water from the reservoirs than normal. That resulted in flooding of areas both downstream and upstream of the reservoirs, including a subdivision chosen Comport Creek Hamlet only south of Hammond's.

That surface area flooded twice. The starting time time, it flooded because rainwater overwhelmed drainage systems and streams. The second time, the Corps had airtight the dams in Addicks reservoir, causing the stored water to support into neighborhood streets.

It's lucky homes didn't inundation the second time effectually, Long said. If the rain had fallen closer to the reservoirs, the situation would have been much worse.

17

Of the 10 largest pools that have accumulated in the reservoirs, nine have occurred since 1990 and six of those were since 2000. Long says that's straight correlated with all the new growth and development.

On top of the balancing act triggered by major storms, the extra water that's accumulated in the reservoirs has strained their earthen dams, which have been considered in critical condition for vii years in big role because of what would happen if they failed. The Army Corps says they are nowhere shut to failure but estimates harm of nigh $sixty billion if a alienation were to occur. More than than 1 meg residents downstream from them would exist impacted.

The more immediate risk, though, is to nearby residents like Hammond who may be flooded during the next large storm. Such neighborhoods are not but at increased risk; Long said they also are adding to the problem because their drainage systems are sending more than water into the reservoirs. Development in the Cypress surface area upstream from the reservoirs is too making things worse.

18

It has led to increased runoff into Cypress Creek during major storms, causing it to escape its banks and spill into 4 other streams on the s side of State Highway 290, in a completely dissimilar watershed. The phenomenon has been called "the overflow problem."

Original plans for the Addicks and Barker reservoirs included a levee that would've prevented the overflow problem and a canal that would accept evacuated more water out of the reservoirs. Those components were dropped due to some combination of fourth dimension and money, Long said — decisions that would come up back to haunt the Regular army Corps decades later.

The overflowing control district has said it will split the $iii one thousand thousand toll to study the impact of development on the reservoirs with the Corps, just Congress hasn't yet authorized the funding. Whatever written report will only mark the beginning of what could exist a long and expensive process; more than studies are likely to exist needed, Long said.

In the meantime, the inundation control commune is taking steps to protect Addicks and Barker from the effects of time to come growth. This year, it strengthened rules for new developments effectually the ii reservoirs and in parts of the Cypress Creek watershed. Developers in those areas must at present account for non simply the charge per unit at which water leaves their lots but also the volume that ends upwards draining into the reservoirs.

Information technology'south a step in the right direction, Rice University's Bedient said, but also "a day late and a dollar short" with the area around the reservoirs already and so densely developed.

The inundation control district also is looking at building another large reservoir to ease the stress on Addicks and Barker. But the agency hasn't officially proposed the project and has no timeline for doing so, commune engineer Dena Green said. That'south in function because of how expensive it will exist, she said.

Bedient said the additional reservoir "is absolutely a disquisitional necessity" if the county wants to avoid some other scenario like the Tax Twenty-four hours flood.

"They have no choice," he said. "If they don't practice that, we're going to get another ane of these, you lot know, peradventure not in v years but ... inside the next decade. It's just absurd."

Longtime problem, Little progress

Houston has been trying to solve its flooding woes since at to the lowest degree 1937, when a letter of the alphabet penned by local officials to state lawmakers pleaded for help and declared Texas' largest urban center "at the mercy of the relentless water."

19

Two horrible storms had struck the urban center in the previous viii years. Flooding, officials wrote, was a "constant menace" — endangering thousands of human being lives and "millions of dollars in private, municipal and other governmental capital investments" and potentially causing "the distress of all of the peoples of Texas."

Later on nearly eight decades of massive engineering projects, incredible technological advances and a flurry of regulations for flood command, that letter even so rings truthful. Just now millions of lives and billions of dollars are at pale.

Downtown Houston during a flood in December 1935. (Courtesy Harris County Flood Control District)

Why has so little changed after and so long?

Information technology's true that Houston is naturally prone to flooding. The "Bayou City" is incredibly flat and near a coast forth a warming ocean. And much of it was congenital before people knew what they know now about drainage and floodplain regulation.

Just scientists say the cardinal problem is that Houstonians have assumed they can simply engineer their way out of flooding.

20

Indeed, Talbott insists that the just solution to Houston's flooding woes is to continue widening thousands of miles of bayous across the region then they can carry more rainwater into the Gulf of Mexico. At a toll of $25 billion, with a electric current spending charge per unit of $80 one thousand thousand a year, that will take 400 years, he said — and Congress has been unwilling to provide any extra funds to speed up the process.

Even then, the widening projects would merely ensure that the surface area'south bayous tin handle 100-yr events — nothing like a Tax Day flood, which Talbott said it is impossible to plan for or prevent.

Experts say that is a sorely misguided view.

"I reject that somebody with the sophisticated resource like Houston couldn't do something," said Chad Berginnis, executive managing director of the Association of State Floodplain Managers.

Berginnis and other experts say Houston-area officials could piece of work to preserve green space; strengthen regulation on development; plan for a changing climate; and piece of work harder to remove the 140,000 homes that remain in the 100-year floodplain.

Other cities are trying those approaches. The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District, Berginnis pointed out, plans to eventually get rid of all habitable buildings in the 100-yr floodplain. And many cities are also realizing they must prepare for more astringent rainfall.

In Florida, the City of Fort Lauderdale's recent vision programme includes an unabridged chapter on climatic change preparedness and resiliency. And Broward Canton, where Fort Lauderdale is located, strictly regulates evolution in areas that are pegged to exist at or below body of water level in the future, said Nancy Gassman, the metropolis's banana public works director for sustainability. After Boulder, Colorado experienced horrible flooding in 2013, the city is working to redesign infrastructure with "permeable surfaces" — surfaces that can blot some floodwater, as opposed to concrete — and leaving more open up space. The idea is to do and then not just with a "100-year flood" in mind, but a more rare flood, such equally what happened three years agone.

"Nosotros don't see an event effectually Boulder in the last thousand years that was as crazy equally that ane. So yes, freak event," said Hayhoe, the Texas Tech climate scientist. "Is Boulder preparing? They're still preparing because they know in a warmer world, the risk of heavier rainfall is greater."

Costello, Houston's flood czar, said he is aiming to secure near $10 million in the next city budget to create a "response team" that would behave out smaller, quick-hit flooding projects. The city likewise secured a $250,000 state grant in August to amend its early warning system.

But the region has many other competing priorities.

"Are we doing everything nosotros tin?" said Radack, the Harris County commissioner. "No, we're not doing everything nosotros can because we still have to pay hundreds of millions of dollars for the hospital district. We still have to build roads. We certainly desire to accept parks."

He as well indicated there was little adventure that the city or county would be able to implement stricter regulations on development in floodplains, fifty-fifty though the neighboring county, Fort Curve, has been able to do so.

Not only are the rules lax, critics say, but also local officials don't always enforce them. Costello, Houston'southward overflowing czar, agrees.

Metropolis of Houston flood arbiter Steve Costello meets with Memorial City residents. (Michael Stravato for The Texas Tribune/ProPublica)

"Some of the residents are saying that we don't have the resources to go out and constabulary what has been done," he said of irresponsible evolution. "If you drive effectually parts of the city, you'll get confirmation of that. ... This is a very big urban center, and we have express resources."

(The inundation control district said information technology has enough of resources to constabulary development in Harris Canton, though experts and residents strongly disagree.)

21

And the Army Corps of Engineers, which regulates development in littoral wetlands, simply has about 10 people in accuse of making certain the rules are followed for all of Texas and Louisiana.

"Our budget is fixed by Congress, and it's been flatlined for iii or five years," said Kimberly Baggette, chief of the regulatory partitioning at the Army Corps' Galveston Commune. (Whether that will change under the new president remains to be seen.)

Texas Congressman John Culberson insisted that the agencies in charge of dealing with flooding in his commune have always gotten the money they asked for. The Houston Republican also said the planned third reservoir would assist the city prepare for a bigger overflowing event.

Simply he believes the Texas Legislature volition have to fund such a project, which the flood control district estimated last twelvemonth would cost hundreds of millions of dollars. Meanwhile, the district has said there is not even a timeline to recommend where exactly to build the boosted reservoir or how to fund it.

Aside from the distant reservoir plans, it remains unclear whether many Houstonians realize that zero is beingness done to address floods like the i that happened on Tax 24-hour interval. Democratic Congressman Al Green said he was counting on his colleagues in the U.S. House of Representatives to fund some key bayou-widening projects in the coming months — though he understands they only aim to protect against much smaller events.

"I'k going to maintain a level of optimism," he said. "We should not have another catastrophic upshot and and then bemoan the fact that we didn't do what we could have and should have done, so that'south an argument that I brand."

At a community clubhouse meeting in Houston this summertime, Costello assured the people in attendance that the urban center was doing everything it could to address contempo flooding bug. The meeting was organized past Residents Against Flooding, the group suing the city in hopes of getting certain flood protection projects built.

Asked in an interview the next day if the city could feasibly protect confronting contempo floods, Costello said, "No."

"I don't remember they were post-obit me as well as I hoped," he said, calculation that once the group gets the project they're pushing for in the lawsuit, "There's even so going to be areas that are flood decumbent and it's still going to exist there."

"I don't think they realize that."

Source: https://projects.propublica.org/houston-cypress/

0 Response to "Why Did Houston Decide to Flood the City Again"

Post a Comment